Pitchfork originally reviewed alternative and indie music, but later expanded to covering Hip-Hop, Jazz, Pop, and Metal, as well as issues of gender, race, and identity in the 2010s. But will diverse content live on following the recent merge with GQ? | Graphic created by Zsana Hoskins

One of the most trusted voices in music will now be merged with men’s style magazine, GQ, after an announcement was sent out to staff on Jan. 17 from Anna Wintour, chief content officer of Condé Nast, the parent company of both publications.

According to The Associated Press, at least 12 staffers were laid off from Pitchfork, including 10 editorial employees, leaving only a permanent staff of eight.

Wintour reportedly kept her sunglasses on in the meeting where she discussed the fate of several music journalists’ careers, calling this move “the best path forward for the brand so that our coverage of music can continue to thrive within the company.”

Pitchfork was founded in 1996 by Ryan Scrieber and has since been named one of the most influential publications in the digital age of music journalism. Acquired by Condé Nast in 2015, the publication began to expand from its indie-focused approach. But now concerns about diversity at the publication are on the rise.

The music industry itself is already lacking diversity, with a 2021 study from the University of Southern California showing that 31.2% of music artists are Black, yet only 4.2% of CEOs, chairmen, and presidents were Black across 70 major and independent music companies. But what happens when our representation in the newsroom is also compromised?

Music journalism veteran, Michael Gonzales, formerly associated with XXL, Vibe, and The Source, believes Pitchfork will never be the same.

“Most of the staff has been fired, so I assume they will be relying on GQ staff and freelancers. Pitchfork is a site I look at every day, but truthfully, I haven’t looked at GQ [the site or magazine] in years,” said Gonzales.

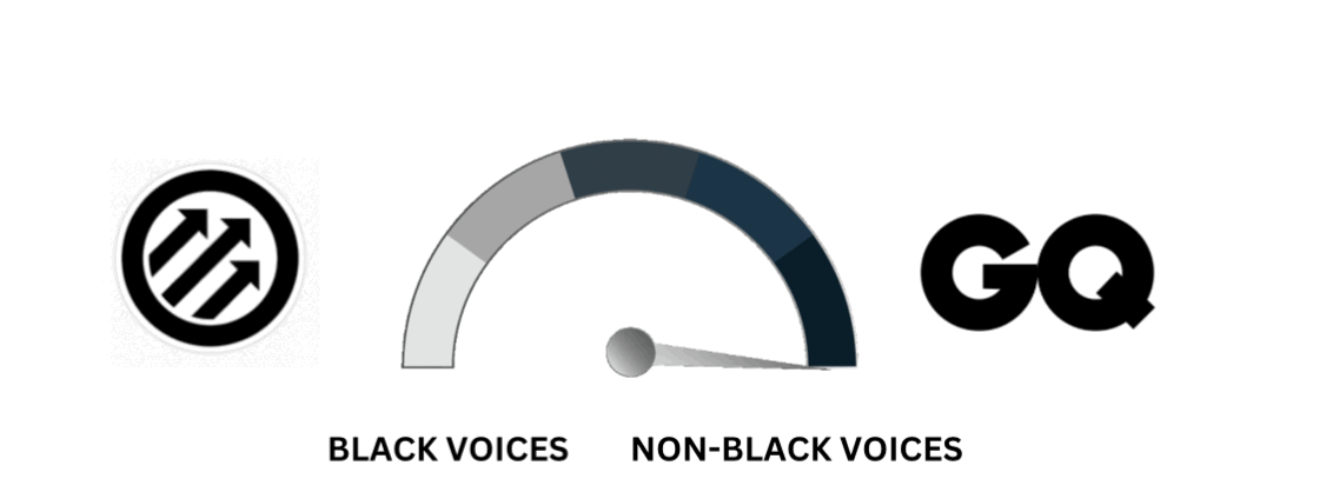

According to Zippia, Pitchfork’s staff is predominantly white and male, with Black people being the smallest minority group (10%) of the newsroom. Data from Zippia also shows that only 7.3% of music journalists in the Pitchfork newsroom are Black. This, combined with GQ’s predominantly white and male readership can almost seem like a threat to authentic Black stories for the publication.

Gonzales worries that this merger mishap could affect the way Black music and artists’ stories are told, especially those who haven’t reached mainstream success. “I think popular rap, such as Drake and Nicki [Minaj] will be fine. But more obscure artists I believe will have a problem as will less popular genres such as jazz, blues, and reissues of older Black artists. Pitchfork did a great job covering older artists’ reissues,” Gonzales expressed.

Taiyo Coates, another freelance journalist who has over six years of experience as a music journalist and concert reviewer for HotNewHipHop, Variety, and more, feels that non-white journalists may lack awareness of the complexities in Black music.

The editorial space in general has been impacted by that [layoffs]. These spaces don’t get refilled by other Black entities. Companies like Vibe, certain branches of The Source, and Complex have been co-opted where there’s no real education on Black music,” Coates explained.

Less Black writers could also mean a disconnect when it comes to music interpretation.

“It’s a perspective landscape that automatically is magnified when it comes to Black music because of the nuances that we talk about,” Coates said about music journalism. “If someone is talking about Noname’s project without understanding the background, there’s now a disconnect for the writer and that also creates one for the audience.”

R&B and Hip-hop freelance reporter Kia Turner, who has written for Rolling Stone, Okayplayer, and others, finds the merger interesting,as GQ isn’t typically a destination for music criticism. She questioned the greater intent on the ongoing trend facing companies like Pitchfork, adding, “I’m more interested in why the big issue across journalism is these corporations and big mega publication dynasties buying out other smaller companies, and the content is dying down.”

Coates also echoed concerns about authenticity., “GQ didn’t get their genesis in music, so now you have Pitchfork working with people who don’t know how to digest music editorial. Authenticity is really a big deal when you merge with any company that doesn’t do what you do.”

Turner referenced when Buzzfeed acquired Complex and how it affected the content and reputation of the company, especially the quality of its music journalism. As smaller companies are bought out, they often shift to covering other topics such as entertainment, film, and even celebrity gossip.

“For music journalists overall, it creates a smaller landscape. We all can’t go to Rolling Stone. We all can’t go to BET. We all can’t go to Vibe. We, as freelancers, can’t infiltrate the spaces because there’s just not enough room for it,” Turner expressed. “All these kids who are going into the media space, I don’t know what to tell them. How are you going to sustain yourself off of your art when the only skills you thought you needed were loving music and writing?”

Many Black music journalists, including Turner and Coates, are mainly concerned that though the state of journalism as a whole is being questioned, Black journalists will remain the ones to get the short end of the stick.

“As far as Black journalists, it makes it harder. Historically, not a lot of us are hired at places like Billboard or Complex. They want to write about Black music, but don’t hire us. This is going to affect journalists hard, but it will hit harder for Black journalists,” Turner said.

Coates is also worried that music journalism may eventually wither away into nothingness.

“Where are the areas that we can go to and feel comfortable in these spaces? This merger doesn’t seem like it is creating more opportunities for Black journalism. Because of the death of physical media as well, we have to find a way to create something of our own or it will just die out.”

However, Coates offers advice and encouragement for Black music journalists entering the industry at such an interesting time.

“Leverage your connections outside of the music space to help you create something inside the music space. Be open to asking a lot of questions.”

Recent Comments