He stood perched atop the steps of the Lincoln Memorial on Aug. 28, 1963. Having been beaten and jailed on a number of occasions, he was now about to deliver one of the most important speeches of his life.

No, the man above is not the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., rather, he is one of the less-heralded planners of one of the world’s most prominent civil rights demonstrations — U.S. Rep. John Lewis, D-Ga.

At 23, Lewis was the youngest of the six planners and the chairman of the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). He is the only speaker from the march still alive.

Contrary to what some may believe, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was organized well in advance and encompassed so much more than King’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

More Than a Speech

For Lewis, that Aug. 28th day was so much more than just a speech. In fact, part of the reason may be that his original speech took some heat for its incendiary wording, claiming that President Kennedy’s efforts were “too little, too late” and comparing the movement’s determinations to Sherman planning to burn through Georgia.

As an excerpt from his speech — which was not taken out — says: “You tell us to wait. You tell us to be patient. We cannot wait. We do not want to be free gradually. We want our freedom, and we want it now.”

“I didn’t like idea of someone asking me to change,” Lewis said.

He constructed his speech with the help of SNCC members as well as two Howard activists and members on the march’s planning committee: Courtland Cox and Tom Kahn.

The Most Rev. Patrick O’Boyle, archbishop of Washington, threatened not to give the invocation at the march and take all of the Catholic attendees with him.

Lewis believed the Kennedy family (President John F. Kennedy and brother Robert, who was the attorney general) had gotten to the archbishop, noting that he was a close family friend.

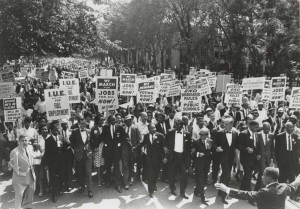

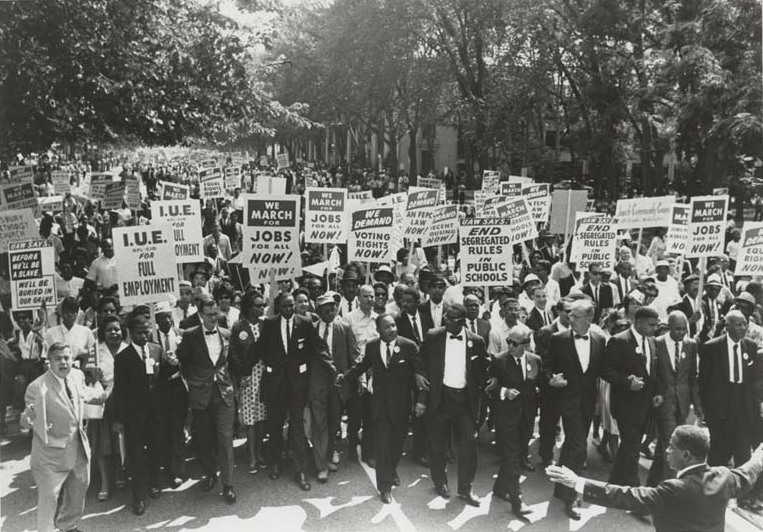

A Flood of People

Prior to giving his speech, Lewis and the other planners were actually late for the march having met with members of congressional leadership earlier that day.

They stepped out onto Constitution Avenue on the Senate side, only to see “hundreds and hundreds” of people flooding down the street from Union Station.

Lewis said it was then that it hit him what kind of turnout all of their planning had led to. He recalls thinking: “There go my people; let me catch up with them. We’re supposed to be leading them!”

They locked arms with the masses, allowing the waves of people to carry them to the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

Lewis pauses to assert that Kennedy made arrangements to quell any violence or crime that resulted from the march including closing all liquor stores, having federal troops lock down the city and shutting down the communications system at the march. None of this had to be used, as the day’s events and festivities went peacefully.

‘I Then Looked Straight Ahead and Just Went for It.’

He described the moments just before taking the podium to speak in front of an estimated 250,000 people — closer to half a million by his estimate:

“I looked to my right and saw hundreds of young people from SNCC cheering, then I looked to my left, and there were young people in trees trying to get a better view. … I then looked straight ahead and just went for it.”

Many people, both black and white, placed their feet in the Reflecting Pool trying to cool off.

“August 28th forced me to grow up.”

Now 73, Lewis says he thinks about the others like A. Phillip Randolph and Bayard Rustin — who is not considered one of the six original planners but was appointed by Randolph to help organize efforts to get people to D.C. — “a great deal.” He describes all of the planning and collaboration as “unforgettable.”

He also thinks highly of King, who was the final speaker while Lewis went third.

A major reason King’s speech gets so much attention is the timing of news coverage. Major media stations joined the coverage just before King spoke. However, Lewis says he has never felt overshadowed by King whom he describes as the “personification of the movement” and the “undisputed leader of Civil Rights Movement.”

“I learned of him when I was 15, then I met him for the first time when I was 18,” he says. “He was a hero and always inspired me.”

With the intonation of a father reminding his child that which he has been told 100 times, Lewis adds that the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, which followed two years later, resulted from the movement because it educated people from all different corners of the country and even overseas to what had been happening to many blacks in America.

Paving the Way

When asked to compare the March on Washington to Obama’s election, Lewis says that he can’t rank them because the efforts of the former helped pave the way for those like President Obama. He considers the president as a good leader, but says some in Congress have set out for him not to succeed.

Lewis attended most of the commemoration events in addition to a number of panel discussions and speaking arrangements.

He was succeeded as the head of SNCC by Stokely Carmichael, a Howard alumnus, whom he credits for being instrumental in the understanding of black power and black consciousness.

Lewis thinks that young black males could do so much more good, given the technology that they now have.

“We didn’t have cell phones or an iPad,” Lewis said. “We had a fax machine.”

“Black males today must pick up where black males left off from the past generation,” he adds. “They should be courageous and bold.”

“Speak up, speak out, show up and show out!”

Glynn Hill is editor-in-chief of The Hilltop, where this profile originally appeared on Aug. 29, 2013.

Recent Comments